In an interview Markus Schmeiduch, winner of the category [the next idea] voestalpine Art and Technology Grant of the Prix Ars Electronica 2014, talks with us how BlindMaps came into being and why submission for Prix Ars Electronica prize consideration was the next logical step for him.

As previously announced, the Ars Electronica Blog will be presenting selected projects that have been singled out for honors by the Prix Ars Electronica this year. We’re kicking off this series with the 2014 recipients of [the next idea] voestalpine Art and Technology Grant: Markus Schmeiduch, Andrew Spitz and Ruben van der Vleuten, the staff of the BlindMaps research project.

As previously announced, the Ars Electronica Blog will be presenting selected projects that have been singled out for honors by the Prix Ars Electronica this year. We’re kicking off this series with the 2014 recipients of [the next idea] voestalpine Art and Technology Grant: Markus Schmeiduch, Andrew Spitz and Ruben van der Vleuten, the staff of the BlindMaps research project.

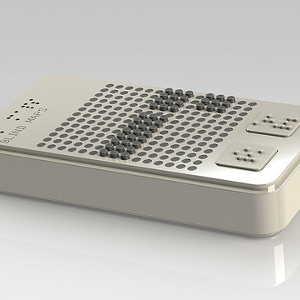

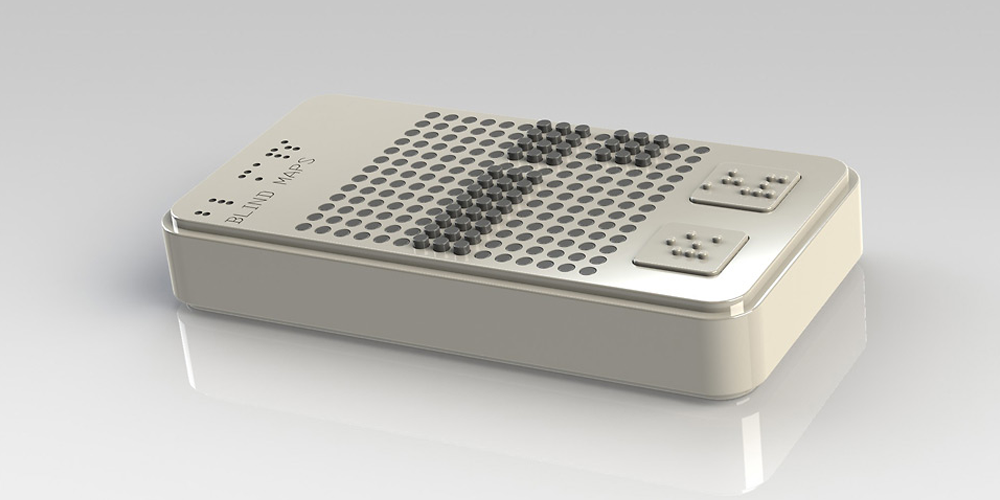

Even for people with good vision, navigation through a big city you’re unfamiliar with can be a difficult task, but for people who are blind or visually impaired, this is a daunting challenge indeed. There are already lots of navigation systems available today, but most of them are based on visual displays. So, BlindMaps is a research project that has taken on the difficult task of developing a navigation system for use by blind and visually impaired men and women making their way though big cities in which they’re strangers. BlindMaps uses a touch-sensitive haptic technology that enables visually impaired people to obtain routing via verbal input. The interface features a perforated screen reminiscent of Braille script. These tiny protruding buttons move and change position, which permits navigation in real time. The decision not to rely on a verbal description of the route was based on the fact that this could prevent the user from hearing ambient noises that are important for orientation. Currently in planning is BlindMaps as a crowd-sourced, navigation-based service. If a problem arises en route, the user could then report it by pushing a button, whereupon he/she is automatically rerouted. The more visually impaired people use the respective route, the more precise the orientation can become.

Winning [the next idea] voestalpine Art and Technology Grant awarded by the 2014 Prix Ars Electronica competition will now make it possible to develop the project further in cooperation with the Ars Electronica Futurelab. This also entails a cash award in the amount of €7,500 donated by voestalpine.

Before Markus Schmeiduch begins his stint as artist-in-residence at the Ars Electronica Futurelab, we met with him to discuss this terrific project. He gave us an account of how it came into being, why submission for Prix Ars Electronica prize consideration was the next logical step for him, and what sort of expectations he brings to the collaboration with the Ars Electronica Futurelab’s staff.

BlindMaps is a very innovative, futuristic project. How did you come up with this amazing idea?

Markus Schmeiduch: It’s an interesting story. I’m originally from Natternbach in Upper Austria, and I’ve attended the Ars Electronica Festival regularly since I was 16. The upshot was that I developed a certain fascination for technology and design, which, in turn, was one of the reasons why I started studying Multimedia Art in Vienna.

My initial contact with blind and visually impaired people came when I was 18 and had a job in a hotel in Gallspach, Upper Austria in a hotel that specialized in blind guests. I was responsible for seeing to guests’ needs and I went along on several day trips—for example, to Linz, Salzburg, the Melk Monastery and along the Danube.

This was really interesting and a completely new experience for me, above all because I was faced with the challenge of navigating blind people through a city. I worked for almost a year in Gallspach before beginning college in Vienna. But ever afterwards, during summer break, I often went back to Gallspach to help out. That was what you might call my introduction to the course material. That’s where I first came to appreciate what it means to be blind and what sort of challenges blind people face when they move about in a big city.

In 2012 I went to Copenhagen to do a master’s program in Interaction Design. There, the very first assignment we got was to ask ourselves was how technology or human-computer interaction can possibly help people manage aspects of everyday life. This was a relatively open assignment, and the idea of being blind was one of the first thing that Andrew, Ruben and I discussed as a team. The idea for BlindMaps than happened rather quickly in our brainstorming session.

Andrew Spitz and Ruben van der Vleuten are also involved in the project. Who’s responsible for what?

Markus Schmeiduch: Andrew and Ruben were my fellow students in Copenhagen and the first phase of the project was also an assignment in conjunction with a course THERE. The goal was to develop a concept and visualize it within 36 hours.

Andrew came up with the idea for a connected device as basis for mobility and worked on the interaction design concept and our video. As an industrial designer, Ruben had already done a lot of work in the medical field, especially in conjunction with designing devices for operations, which means he had a lot of experience with technology and hardware. For our project, he programmed the Braille interface in the software. I brought in the practical learnings due to the experience I had with blind and visually impaired people and we three together then produced the detailded interface concept and the video to visualize our idea in a matter of 2 nightshifts.

How did the history of the project go on from there?

Markus Schmeiduch: After we completed the university assignment, we put the video online, and right away we were featured on various blogs and we got quite a bit of positive feedback. A lot of people wrote to us that either they’re blind or they know someone who is, and it would be great if our project could really be implemented. That’s when we first realized that there really is a need in this area.

In 2013, I submitted the project to Creative Region Upper Austria, and I was accepted by the Cross Innovation EU subsidy program, which made it possible for me to continue work on the project in Berlin and Amsterdam. In Berlin, I met frequently with blind and visually impaired people and discussed the project with them. And we did a lot of brainstorming about how BlindMaps could function. In Amsterdam, where Ruben and Andrew now live, we built the first prototype with the help of a 3-D printer. Then I took this prototype back to Berlin and tested it together with blind people.

Andrew Spitz

Andrew Spitz

How did you get the idea of submitting the project to Prix Ars Electronica?

Markus Schmeiduch: Since I’m a big fan of Ars Electronica, being a Prix Ars Electronica prizewinner has always been a goal of mine. There were no big tactical considerations behind the entry; it was just the next logical step in developing the project. What most attracted us was the prospect of financing from [the next idea] voestalpine Art and Technology Grant, because what we need to move this project forward is not only publicity but also people who can support us in concrete ways. And since the Futurelab combines both aspects, Ars Electronica is exactly what we’re looking for.

What are your expectations from this collaboration with the Ars Electronica Futurelab?

Markus Schmeiduch: I’ve already attended an initial meeting to discuss my residency at the Futurelab, and it looks really promising because the Futurelab people I’m going to be working with have just the right background for a project like this.

In any case, we hope we can take the next big, important step with BlindMaps. At this point, we have the concept and the first prototype. Here, we want to get started collaborating with the Futurelab and then get back to working together intensively with blind and visually impaired people, so that the insights this yields can be used to further improve the concept. After that, we want to move in the direction of technology and try to produce an enhanced prototype that, if all goes well, we’ll be able to present this coming fall at the Ars Electronica Festival. I feel this would be a big step forward.

And I hope that this will have brought us to the point at which we can give some thought to realization. Of course, this isn’t a project that can be implemented overnight. Some of the technology we need is still highly experimental—for instance, Galileo, the EU counterpart to America’s GPS. We’re very much interested in this navigation system because it works much more precisely than GPS. It’s exact to within half a meter, as compared to four meters with GPS. Needless to say, for BlindMaps, the precision of the navigation data plays a major role—after all, it makes a big difference if a person’s standing on the sidewalk or is already in the middle of the street.

So that means we still have a few technical hurdles to surmount. But this is a long-term project. We’re working with Creative Commons, with an open source license, which means that anyone can use what we come up with and develop it further in their own project. There are several other projects pursuing a goal similar to ours, and I won’t be the least bit disappointed if someone else brings their project to fruition before we do. For me, the only thing that’s important is for blind and visually impaired people to get help.

Are there any other technical challenges that this project has to face?

Markus Schmeiduch: Yeah, there are a lot of challenges in this project! The precision of the navigation is definitely one of the most important and most difficult. But if Galileo actually delivers on its promises and really is available in 2017, then we’ll be able to use it as a basis for BlindMaps.

The degree of detail of the maps is also important. Here, we’ll probably go with Open Streetmaps, but cooperation with Google or Microsoft would also be a possibility.

Another technological challenge is the white cane that a blind person uses. Here, the question is the extent to which we can miniaturize the feedback mechanisms of the Braille lines so that they, together with the battery to power them, can be built right into the cane. The challenge here is similar to the situation with cell phones, which means that there’s quite a bit of technology in this area that we can use.

Even though you work closely with blind people, have you also tested the project yourself?

Markus Schmeiduch: Of decisive importance is to prevent BlindMaps from becoming a case in which the designer and the engineers come up with solutions and then attempt to force their own ideas and approaches down users’ throats.

I’m not blind or visually impaired, so I can only attempt to understand their situation. Therefore, it’s very important for us to work together as much as possible with blind and visually impaired people. We’ve repeatedly conducted tests in which we blindfold ourselves to get a feeling for what it’s like to be blind. We could even go so far as to conduct this experiment for a whole day.

Could you imagine attempting this for an entire day?

Markus Schmeiduch: Yeah, sure. There would definitely be a lot of things in everyday life you wouldn’t be able to do alone; you would need another person to accompany you. In any case, it would be worth a try. This would be a good idea for the project this summer.

Markus Schmeiduch will carry on work on the BlindMaps project as artist-in-residence at the Ars Electronica Futurelab from July 28th to September 12th. We’ll provide updates about his progress here on our blog. Plus, the project will be presented at CyberArts at the Ars Electronica Festival.