The Artificial Skins and Bones project seminar conducted by Prof. Mika Satomi and Prof. Wolf Jeschonnek is one of this year’s two recipients of a STARTS Prize awarded by the European Commission. Here’s a briefing on the Berlin Weißensee School of Art and work being done there.

“Nature’s patterns, structures, and functions are an endless source of inspiration” is stated right up front on skinsandbones.de, the Artificial Skins and Bones project seminar’s website. And we sure don’t have to look far to get inspired. The human body itself is an inexhaustible source of inspiration, especially when it comes to making even the slightest effort to restore a bodily function by technological means. In cooperation with prosthesis manufacturer Ottobock, undergraduates conducted workshops, interviews and research, and channeled the insights they gained thereby into their projects. Here, we present the nine works that were produced by participants in this seminar led by Prof. Mika Satomi and Prof. Wolf Jeschonnek at the Berlin Weißensee School of Art, and scrutinize why the collaboration of art and industry worked so well in this model project—so well, in fact, that Artificial Skins and Bones has been honored by the European Commission with a 2016 STARTS Prize.

“Visible Strength” by Lisa Stohn and Jhu-Ting Yang is a prototype inspired by the octopus. The designers created a skin-like material that’s capable of altering its color or pattern at will through muscle activity.

Nature is a rich source of inspiration for designers. Why did you focus this project seminar on the human body, particularly the skin and bones?

Wolf Jeschonnek: Our partner Ottobock was involved in conceiving this project right from its inception and we deal with the digitization of product development and production, so the theme was pretty much self-evident. But it wasn’t actually so tightly focused—the students were given latitude to interpret “skin and bones” quite figuratively. For us, skin and bones constituted a metaphor for rigid structural elements (bones) and flexible membranes (skin), each of which could be equipped with sensors and actuators to enable them to interact.

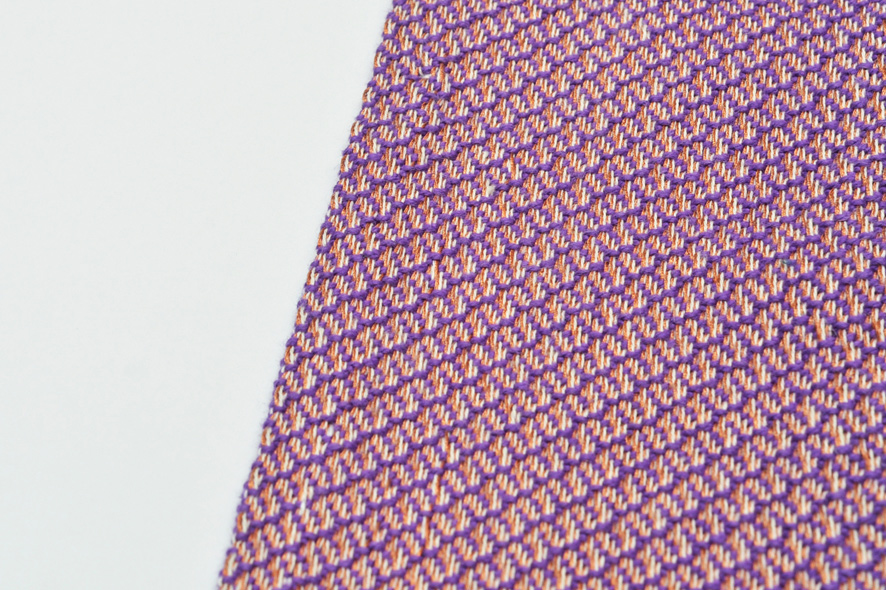

In creating “Trans.fur,” Karina Wirth and Natalie Peter drew their inspiration from the human body’s most versatile organ, the skin. They developed textiles with variable mesh sizes that, like human skin pores, can reduce moisture permeability through guided contractions.

What led up to holding this seminar at Berlin Weißensee School of Art in cooperation with Ottobock and Fab Lab Berlin? What were your aims?

Wolf Jeschonnek: Weißensee, Ottobock, Makea Industries and Fab Lab Berlin are partner in Open Innovation Space. This seminar was one of the first joint projects, and the objective was to explore collaboration possibilities within the framework of this partnership. And the format of a semester project is very well suited to this because it gets all the partners involved but has more of an experimental character and thus doesn’t have to fulfill the requirements of a regular research or development project.

“Technology, Temperature and Textiles” by Stephanie Nattrass is a material experiment to create a prototype that can detect changes in ambient temperature and generate heat.

During the semester, the students also visited Ottobock’s R&D division in Duderstadt, Germany and spoke to technicians, physiotherapists and amputees. How did these discussions influence what happened thereafter?

Wolf Jeschonnek: Like I said, the assignment had not been restricted to the human body, but I think that these encounters with prosthesis wearers as well as those who produce them shifted the focus in this direction. Plus, there was a lot of professional input for these projects, so they could be developed freely and nevertheless oriented on real-world problems. Furthermore, the theme became much more tangible, and thus this form of encounter contributed mightily to making for a dispassionate, professional mode of dealing with the subjects of amputation and being handicapped.

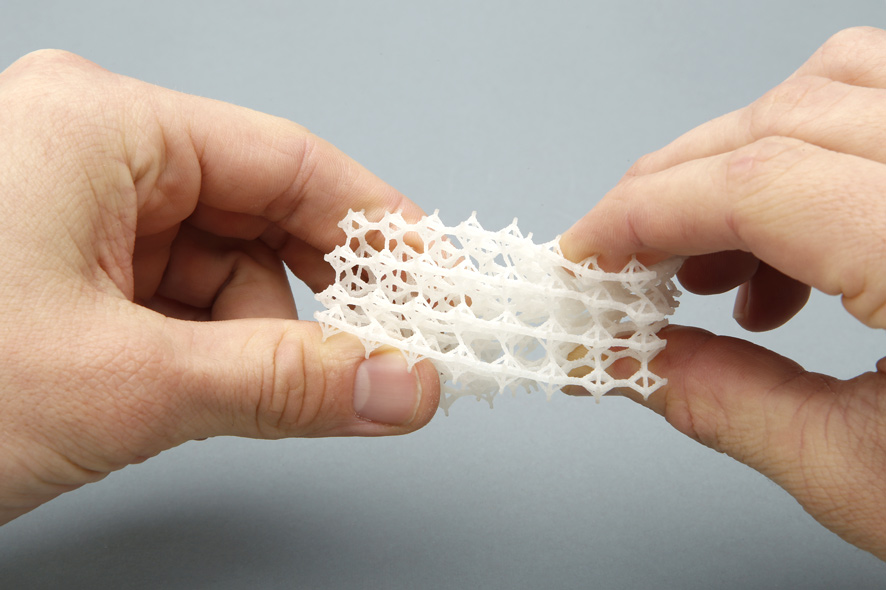

Babette Wiezorek’s “Naturanslations” explores the character and potential of organically inspired material architecture with the help of algorithmic shape sculpting and 3-D printing.

Artificial Skins and Bones is a best-practice example of how well collaboration among science, technology and art can function. What do you see as the advantages of this type of cooperation?

Wolf Jeschonnek: I think the framework conditions were close to optimal. All the partners and the chief protagonists are located in the same city only a few kilometers from each other. Since we were already partners in OIS, there was very open and constructive collaboration right from the start and very little wasted effort due to friction. The combination of an industrial enterprise, a small firm, a university and a community was an excellent mix, and that yielded a clear distribution of assignments and roles.

“Audio Gait” by Agnes Rosengren and Bernardo Aviles-Busch translates walking motion into audio feedback to support a wearer’s sense of balance when walking. The portable system and is an easy learning aid for shin-prosthesis training.

Wolf Jeschonnek: As guest professors, Mika and I had a great deal of freedom as far as conception and implementation was concerned, both from the university as well as the practice partners. WE had the opportunity to stage workshops with outside experts, which gave us the benefit of a lot of professional expertise, both with respect to substantive topic and for the documentation. And an ample budget was placed at our disposal.

“Active” by Hans Illiger supports the rehabilitation process of lower limb amputees. It utilizes sensors to capture movement data and makes available video recordings for independent training.

Wolf Jeschonnek: And above all we had a highly committed and talented group of students, both interdisciplinary and international—four areas of specialization and five countries. The teams ultimately performed the lion’s share of the work and, with their ideas and concepts, made the most important contribution to the project’s success.

The “Shortcut” armband developed by David Kaltenbach, Maximilian Mahal and Lucas Rex for upper-limb amputees picks up sensory muscle impulses of the phantom limb and translates them into commands for contactless, intuitive computer controlling.

“Tactile Communication” by Nina Rossow allows passive tactile recognition of materials when direct contact is not possible and also simplifies descriptions in pain diagnostics.

“The Aesthetics of the Uncanny” by Carmina Blank and Sandra Stark analyzes the design of prostheses in light of the Uncanny Valley hypothesis, which states that the more human-like prostheses look, the more appealing they are, but too much likeness to real human limbs freaks people out.

“Artificial Skins and Bones” isn’t alone; “Magnetic Motion” by Iris van Herpen has also been singled out for recognition by the European Commission with a 2016 STARTS Prize. Go to starts-prize.aec.at, to find out more about the prizewinning projects as well as the Honorary Mention recipients honored in conjunction with the 2016 STARTS Prize competition staged for the first time this year by Ars Electronica on behalf of the European Commission. And keep in mind that the STARTS Prize will be a high-profile presence at the 2016 Ars Electronica Festival from September 8 to 12, 2016, in Linz, in the form of exhibitions and speeches.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 732019. This publication (communication) reflects the views only of the author, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.