An Introduction to hearing

Our world or, rather, the one we live in (after all, who says it’s definitely ours) can be perceived in many different ways. These modes of perception are, for one thing, highly species-specific—the mole is said to have miserable eyesight; the fly’s is multifaceted; and what the dog picks up with its nose is way beyond the ken of human beings. The sense of touch can play a major role or none at all. As for hearing, there are tremendous differences here too.

Sam Auinger, the 2011 Featured Artist, is a friend of long standing who describes Ars Electronica as one of his artistic cradles. His work deals with how we hear the world, how we perceive it acoustically. Our auditory capacity occupies the center of his attention (though our ears are mounted way off to the sides of our head, which, of course, is essential to their working properly), and he attempts to register—above all to capture and reproduce—what occurs when we listen closely, or don’t for that matter.

The way hearing functions is essentially the same for all people. On the outside of our head, most of us have two ears: one left; one right. This is where sound—that is, sound waves and thus something physical, more or less condensed—enters the body and is focused by the ear’s shell-like form. And here, something pretty nifty occurs: Depending on whether the sound waves enter the ear from the front, the side or the rear, they sound different. They’re filtered, and thus, even at this early stage, we’re able to get oriented horizontally. Vertically is a little more complicated.

Next, the sound encounters the eardrum, which has several functions. For one thing, it protects the inner ear from excessive acoustic pressure; if it’s too much, this membrane can tear and then there are problems—inflammation, fluid discharge, little things like that. The eardrum also transmits sound-induced vibrations to the hammer, anvil and stirrup, tiny bones that are something like a mechanical transmission forwarding the sound to the inner ear, the spiral-shaped cochlea, where the perception of the individual frequencies, the various pitches, takes place. This is the location of the basilar membrane, a tiny foundation upon which hair cells (stereocilia) are arrayed—a certain number for each frequency; most of all in the range of the human voice so we can communicate effectively with one another. Here, a sound wave, depending on its frequency, causes particular hairs to tilt, and they, in turn, send an electrical impulse to the brain, which then says: Aha, that was an A! (If you have perfect pitch; if not, you still hear the same thing, but you just don’t know what key it’s in.) Deep within the ear canal of a disco habitué, it can happen that these tiny hairs issue a message of their own: You know what, if it’s noise you like, my friend, then I can arrange for you to hear it incessantly. And that’s how tinnitus announces its arrival.

So much for the functional principles of hearing.

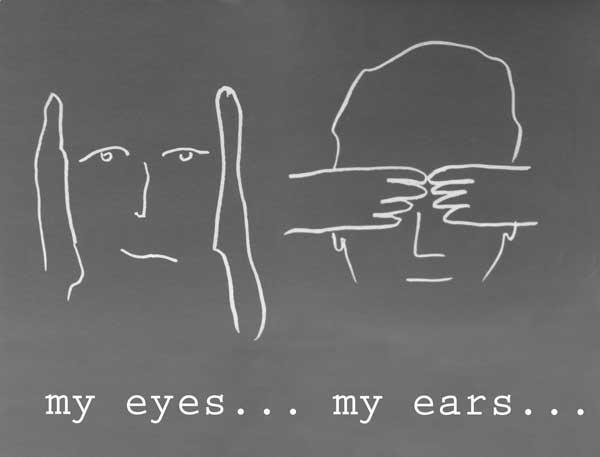

Sam Auinger, My Eyes, My Ears

Sam Auinger, My Eyes, My Ears

What Sam Auinger does is deal with the psychoacoustic side of this story. It’s like this: from a technical perspective, we all hear pretty much similarly; but in actual practice, of course, differences manifest themselves. And the artist investigates these differences. Scrutinizes tensions—not only acoustic oscillations but also the divergences between what we perceive visually and what is heard. Like dogs that sound like elephants, or singing bridges.

In conjunction with the Ars Electronica Festival, Sam Auinger will be tuning in to the wavelength of Linz’s New Cathedral and, for one night, making it the setting of his artistic endeavors. An interview with the artist will soon be posted on this site. An overview of his oeuvre to date is available online at www.samauinger.de.