Renaming the City

mit Marcus Neustetter, Stephen Hobbs und Ars Electronica

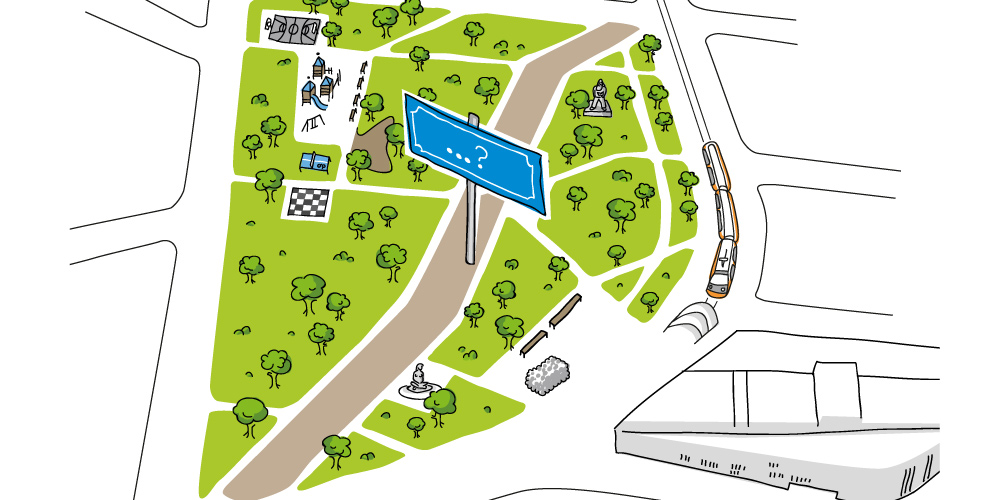

Sie kennen den Linzer Volksgarten? Dann kennen Sie auch den großen Weg in diesem Park. Dieser Weg hat noch keinen Namen. Haben Sie eine Idee, nach wem oder was dieser Weg benannt werden soll? Senden Sie uns eine E-Mail an renamingthecity@aec.at oder eine SMS an +43 699 1778 1558!

Namensvorschlag mailenIm Rahmen der Ars Electronica 2015 beschäftigen sich die südafrikanischen Künstler Marcus Neustetter und Stephen Hobbs mit dem Linzer Volksgarten. Unter dem Motto „Renaming the City“ laden sie in Linz lebenden Personen ein, Namensvorschläge für die Spaziermeile zu machen, die den Volksgarten von der Goethekreuzung bis zur Ecke Volksgartenstraße-Kärntnerstraße durchquert. Ziel ist es, Menschen mit als auch ohne Migrationshintergrund zu motivieren, sich am Prozess der Namensgebung zu beteiligen. Gemeinsam mit Ars Electronica wollen die Künstler so eine Willkommenskultur fördern, die für einen funktionierenden urbanen Raum – also auch die Stadt Linz – künftig immer wichtiger sein wird.

The Trinity Session – Stephen Hobbs and Marcus Neustetter

With the contribution of Jochen Zeirzer, PANGEA, Integrationsbüro der Stadt Linz and the boarder network of the participating immigrant organisations and Linz community.

Marcus Neustetter über das Projekt „Renaming the City“

When I first walked through the Volksgarten in Linz I did not hear any German being spoken. Yet the stories on the local news detailing the grim experiences of refugees and migrants living in Linz stood in stark contrast to the diversity I was experiencing in this public space. It reminded me of home Johannesburg, South Africa, where overt xenophobia is felt in everyday mistreatment of foreigners that culminates in regular violent outbreaks. Sadly, our South African borders and behaviors have come to send a strong message of rejection, in a time of great need, to the people of the nations that so generously accepted and aided our exiled community. My experience in the Volksgarten highlighted connections between the South African apartheid experience which, much like the Austrian Nazi history, lingers on in subjective memories, through continued spatial injustice, and in pervasive othering. Indeed it is this that drives our artistic practice of socially engaged public art towards understanding whether there is a utopian inevitability of global integration.

Is it that far fetched that the Champs-Élysées in Paris will one day host the cultural attractions of a francophone African city? Or that foreign culture and integration will need to go beyond the cliché of the Chinese restaurant or Kebab store on the Hauptplatz? Can we imagine a future where a city’s commitment to global growth and integration will be measured through the way in which they welcome the newcomer into their public spaces? It will start to define a city’s wealth not for its infrastructure and its economic boom, but for its tolerance, engagement and cultural diversity. Dialogues held with immigrants in Linz produced both grueling tales of an arduous journey, as well as positive anecdotes of the support they have received. However, it is apparent that we still seem to be a long way from the welcome we would like to receive if the tables were turned.

Both Stephen and I are white born South Africans with European family roots. South Africa is home. Johannesburg is home. Yet, with the changing population in our city from black South Africans that moved into the city at the end of Apartheid and the more recent influx of refugees and migrants from the continent we are suddenly considered the tourists in certain spaces of our city. While we constantly question our presence and foreignness in a radically changing space, I did not expect to be reminded of the questions I ask myself on the streets of Johannesburg, while in Linz. My German speaking, male whiteness was just as alienating in the refugee and migrant circles in Linz I was not painted with the brush of the tourist, but of the local, that might or might not be accepting of the foreigner.

Back home we look to the public spaces in which we operate and we try to make sense of how these spaces exemplify the layered history of our country, a sense of ownership, control and alienation. Our artistic interventions in public have helped make sense of these charged spaces. These interventions are both in the creation of permanent public artworks, as commissioning agents for the city, as well as temporary activations towards our own practice. Each project gives rise to new opportunities for engaging the new inhabitants of the city and getting to know our own neighbors.

Bordering on social practice and cultural activism these artistic interventions help illustrate a future reimagining of public space as a host for various cultural activities. Witnessing Johannesburg change as a city has provided much inspiration in exploring other options and tools for meaningful engagement and creating a sense of city ownership for its diverse public. On a national level, streets, parks, and public areas, are being renamed to celebrate local post-apartheid heroes and to attempt to create new identification with the very public spaces that were once only accessible to a few.

Our project for POST CITY – Habitats for the 21st Century, responds to these very conflicts. It attempts to bring some of our processes for engagement and place making from home into a context that faces similar challenges. The primary intention of our project is to permanently rename the pedestrian roads in the Volksgarten. The new names will be based on incorporating names proposed by immigrants in Linz a symbolic act that hopes to establish a social and political consciousness around ownership and inclusivity. This act is not only a conceptual link back to the transformations of public spaces where we come from, but an outcome driven process that forces locals to engage and include those that are often marginalized. In developing the relationships with communities that have had to struggle with acceptance in Linz, leading up to the festival, there will be attempts to connect through positive gestures. One of these gestures originated in the realization that many immigrants leave their homes in Linz during August to holiday in their previous homes. On their return, they will be met with personal gestures of welcoming by strangers volunteer Linz inhabitants. „Welcome home“ signs in languages appropriate to the arriving travelers will be held by local people offering a warm handshake or maybe even baked goods to a surprised neighbor who has never experienced welcoming in the city before.

For the festival, Linz will be mapped out in the large Post City venue. It is the artists’ intention to ‘capture’ a piece of public space and present it in this venue. The focus area of our renaming exercise, the Volksgarten public park, will feature in the space not only as a drawing on a map, but as a feature to be experienced. The mirroring of this ‘captured’ space within the building, hopes to draw attention to the real park and its activities, as well as create opportunities to play with different parts of the park. Representing it so much larger and more real than the Hauptplatz in the map elevates its importance. In addition, it magnifies the people in it, as culturally diverse as they are, with their daily activities and exchanges. As part of the Post City Volksgarten experience, visitors will be able to contribute to the space by sharing their ideas for new names of the paths. This will become a collection point of public squares and street names emanating from various languages, cities and personal references and journeys.

These choreographed acts are a small attempt at re-imaging the future city, not in the sense of futuristic buildings and transport systems, but in simple gestures of naming ones everyday space, fostering a sense of belonging and ownership to that space, and forging neighborliness between global citizens.