The city, it would appear, is humankind’s most successful survival strategy, and still our greatest social experiment. The Digital Revolution has imparted a new dimension to this experiment.

Half of All People Today Live in a City

Around 1900, approximately 10% of the world’s population lived in cities. In 2015, the figure has exceeded 50% for the first time—54% to be exact. They use 80% of all energy resources. And their numbers are steadily rising—human beings spurred by hope to survive, to find a better way of life, and to live a lifestyle of their own choosing.

(Photo: Library of Congress / Alphonse Liébert)

The City as Symbol

But cities haven’t only been places that promised security and prosperity; they’re also symbols of freedom and progress. And they’ve always been flashpoints of all the social conflicts that humankind has had to manage in every epoch. The buildings we’re erecting now and the traffic arteries we’re laying out constitute the cityscape of the 21st century, and also determine coming generations’ quality of life.

(Photo: Zara Seemann)

Urban Chances and Conflicts

How we now implement architectural measures to configure the public sphere, participatory models to bring about transparency and integration and, above all, to whom we actively entrust or passively cede the responsibility to do so—these are decisive determinants of which opportunities and which conflicts and crises the 21st century will bring.

(Photo: Vincent Callebaut)

So what will it look like, this city capable of dealing with what the 21st century dishes out? In other words, what will our habitats look like after we’ve gone through the Digital Revolution, when the global shift of political and economic power has taken hold, and climate change really gets down to business? POST CITY is the urban sphere afterwards—the city in the wake of all those changes that will perhaps constitute the greatest and most momentous upheaval in recent centuries. This is a development that some call a looming crisis and others see as the dawn of a better day.

Ars Electronica 2015 is focusing on four thematic clusters in order to consider, from both local and global perspectives, how developments—those already in progress and prognosticated shifts—will be changing how our cities look and function:

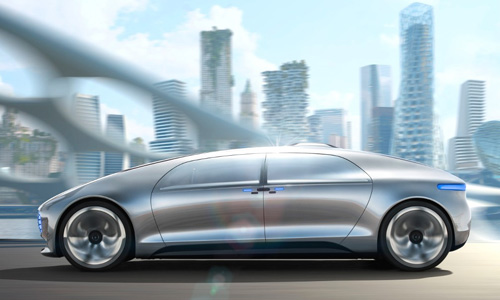

Future Mobility

The city as transportation hub

Future Work

The city as workplace and marketplace

Future Citizens

The city as community

Future Resilience

The city as stronghold

Future Mobility

Mobility of People, Things and Data

Photo: Mercedes-Benz

Photo: Mercedes-BenzFuture Work

Work and Joblessness in the 21st Century

Photo: ABB

Photo: ABBFuture Citizens

Open Society or Global Domination by the Internet?

Photo: Andrew Regan

Photo: Andrew ReganFuture Resilience

Refuge and Resistance

Photo: Dmitry G

Photo: Dmitry GThe epithet Digital City has been superseded by Smart City, but the question of how to fabricate the digital equivalent of a city remains unanswered. Perhaps we have to call into question our previous conception of a city as a geographic conglomeration of resources, and consider the internet itself as the megacity of the future.

Gerfried Stocker (AT)

Gerfried Stocker is a media artist and telecommunications engineer. In 1991, he founded x-space, a team formed to carry out interdisciplinary projects, which went on to produce numerous installations and performances featuring elements of interaction, robotics and telecommunications. Since 1995, Gerfried Stocker has been artistic director of Ars Electronica. In 1995-96, he headed the crew of artists and technicians that developed the Ars Electronica Center’s pioneering new exhibition strategies and set up the facility’s in-house R&D department, the Ars Electronica Futurelab. He has been chiefly responsible for conceiving and implementing the series of international exhibitions that Ars Electronica has staged since 2004, and, beginning in 2005, for the planning and thematic repositioning of the new, expanded Ars Electronica Center.

Christine Schöpf (AT)

Since 1979, Christine Schöpf has been a driving force behind Ars Electronica’s development. Between 1987 and 2003, she played a key role in conceiving and organizing the Prix Ars Electronica. Since 1996, she and Gerfried Stocker have shared responsibility for the artistic direction of the Ars Electronica Festival. Christine Schöpf studied German & Romance languages and literature and then worked as a radio and TV journalist. From 1981 to 2008, she was in charge of cultural and scientific reporting at the ORF – Austrian Broadcasting Company’s Upper Austria Regional Studio. In 2009, Linz Art University bestowed the title of honorary professor on Christine Schöpf.